Interview with Rashi Rohatgi

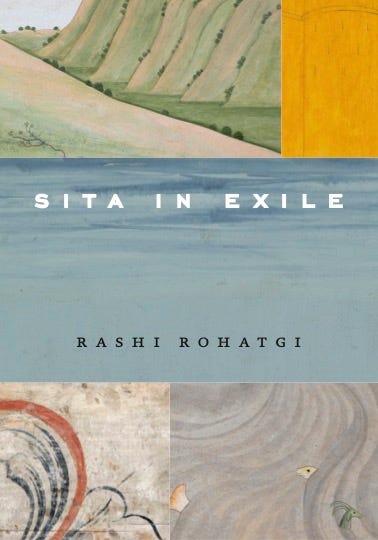

If you’re looking for a beautiful slim book to gobble in a day, I recommend checking out Rashi Rohatgi’s Sita in Exile. Drawing upon Hindu mythology, this lyrical novella tells the tale of Sita, a second-generation American who moves to the Norwegian Arctic. Exploring relationships, migration, and brown motherhood in Europe, Sita in Exile is a gorgeous and thoughtful novella.

I’m going to quote Vivek Narayanan’s blurb because it’s stated much more eloquently than I can: “Sita is in exile; or at least, she is away, existing in a place of alienation, treacherous and insidious for all its comforts, much like that other Sita—those other Sitas—of South Asian epic, whose shadow might be, or vice versa. Flirting with the conventions of fiction but simultaneously myth, and also faith sung between temple and mosque, and working in the margins of epic to unfold an equally vast and unsettling interior space, this novella is a powerful knitting, patient, still and strange.”

Wow, right? I’m pleased Rashi agreed to this interview!

Did you ever doubt this book would be published?

When I started writing Sita in Exile, I decided that this would be the book I wrote in community. I was used to reading fiction and feeling like a part of the community that way, with writing being something I withdrew to pursue; I wanted to switch that up. Participating in writers’ conferences, doing more reviewing and editorial work for journals, publishing excerpts of poems and stories related to Sita in Exile, I was ready to defend my new, louder presence. Except it turned out that the authors I’d been speaking to in my own head were mostly generous and welcoming: the workshop leader who let me know up front that my writing sample was enough to warrant a letter of recommendation from her, so what came next could be a real conversation instead of an interview-lite, the journal editor who not only took my opinions into account but let me lead on enough projects so that when she withdrew to write I was prepared to take over her role (I’ll refrain from naming people in this answer in general, but if you like the vibe of Sita in Exile, please do read Waxwing, where I’m fiction editor), the anthology publisher who paid us authors enough to cover submission fees for a year. I took on more manuscript development work and discovered some brilliant authors that way whose work I hope you’ll all be dazzled by one day soon. I hung out on Twitter and had virtual chai dates where we swapped drafts and stories about how we’d gotten here, wherever ‘here’ was. I submitted this book to contests and presses that seemed like a good fit (and it was, in fact, published as the result of one of these, as part of the Miami University Press novella prize). Overwhelmingly, though, I found so many of us readers, extending ourselves with whatever energy we could spare, whether it came naturally to us or not, creating space for one another’s writing. I’m a writer comfortable with my own ear and my own instinct; I would have written this book if I’d never ventured out. But I also have lots of shelved writing that I know is good but don’t have the energy to fight for, and being a part of the writing community gave me the energy to carry Sita in Exile through to readers, never doubting that I’d see it published.

Can you share any tips or tricks for staying motivated?

Although Sita in Exile asks questions about vocation, there are no scenes of Sita actually working in the book. In part this is because I wrote it during a period where I was faced with relentless racism at work, and Sita in Exile was itself the motivator to keep going despite those setbacks (because, as an academic in an Arts faculty, part of what I was getting paid for was to write the book, I didn’t want to stop getting paid to write the book before I was finished with it). I wrote my first book (Where the Sun Will Rise Tomorrow, about teenage female revolutionaries during the Bengal Partition in 1905 India) during a period when we weren’t able to access childcare, in very disciplined two-hour chunks in the evenings, and while clearly both ways of writing are possible, and I did have the second-book-stress that people talk about, I don’t know that it does anyone any favors to ignore the fact that it’s a lot easier to write a book when there are external motivations. And when you have the funding for the internal motivators as well: my only tried-and-true response to any setback, creative or otherwise, is to flood my senses with rich food, with beautiful prose, with the smell of the sea and the sound of the waves and grains of sand underfoot.

Any reading recommendations?

Since a good friend of mine, the magnificent Prachi Gupta, started working on her memoir (They Called Us Exceptional, coming out in August), I’ve been thinking more deeply about what memoir is, what it does, and how it reaches me as a reader. As such, there is one memoir in paritcular I’m eager to jump into: Noreen Masud’s a flat place. Masud’s memoir is described as connecting the British flatlands landscape to her own experiences with CPTSD, which sounds exceedingly relevant to me, a person who has just written a book about an autistic grief in the Arctic.

Can you recommend a song that ties into your novel in some way?

There were three songs that, wherever I hear them, will always take me right back to northern Norway during the early days of the pandemic. The first is “Habibi,” by Ricky Rich and ARAM Mafia. Northern Norwegian has more in common, aurally, with Swedish than with the Oslo-centric dialect we heard on TV or on the radio, at least for someone hearing the pronunciation with an American ear, and I can imagine Sita hearing this song (it was everywhere), wondering if she could ever be dangerous and mad in a glamorous way that would catch the eye of a cute rapper, instead of increasingly mentally unstable in a way that her partner doesn’t really know what to do with.

The second is Courtney Barnett’s “Depreston,” which is about the Melbourne suburbs, I think, but so much of Sita’s internal monologue is based on the train ride between Champaign-Urbana and Chicago, a ride I took often and which felt like it was slowing warping my brain into something beyond recognition. If Chicago is The City to you, then obviously northern Norway is going to feel like the ultimate distant suburb. Like many brown Americans, I grew up in the suburbs in a place that I recognized as properly idyllic if I were a completely different (and white) person, and I wanted to explore how that rubs up against the experience of being able to sit out the pandemic in this fjord-laden paradise, with the freedom be outside and an outside worth exploring.

Finally, this last one is a little hokey, but when I first moved to northern Norway, the only Norwegian person who was kind to me was this one neighbor. Unlike a lot of people who’d jump in with these absolutely impossible suggestions of where I should take my baby, he never offered advice, nor did he ask where I went when I finally got the wherewithal to explore on my own. It turns out the joke was on me – after he died I learned he was this hugely famous singer, and one of the places I’d ended up spending a lot of time was a beach he’d basically epitomized for the whole country in the song “Mjelle.” But it was a happy joke – I’d assimilated, in this one little way, without all of the horrible interactions that are usually forced about migrants. Sita has these little moments, too, and she’d love this beach.

Thank you, Rashi!